Excerpt from an essay

by Sue Hubbell(The New Yorker - Onward and upward with the arts)

December28, 1987

|

Because, as a beekeeper, I spend a portion of my workdays

at the edge of entomology, thinking about bugs and trying to figure out

what they are up to, friends from more acceptable trades are constantly

sending me clippings about insects and telling me funny bug stories. It

is their attempt to keep in touch with my entomological half, which they

consider quaintly charming but a bit mad.

Not 1ong

ago, I realized that in among the piles of clippings reporting bizarre

incidents?like one about a man in

Florida who pulled out his pistol and shot himself in the leg to kill an

(unidentified) bug that was crawling up it?were

lots of stories about people committing art with insects. The clippings from

art magazines and newspaper art columns indicated that the critics were taking

the individual artists seriously?too

seriously?but that none had grasped

the fact that each show was more than an isolated event. I've discovered a

trend, a movement, and I'm going to claim a discoverer's privilege and name it:

Bug Art.

There are straight representations.

Terry Winters, a New York artist, paints insects on canvas, for instance. Some

venture further and use bug parts. In Beijing, Cao Yijian takes cicadas apart and

reassembles them as three-dimensional figures. In New York, Richard Boscarino

uses whole (though dead) cockroaches to create what he calls still-lifes. In

Los Angeles, Kim Abeles has made what she calls a metaphor for rush-hour traffic,

in her "Great Periodic Migration," consisting partly of cicada

shells. A Japanese artist, Kazuo Kadonaga, has live silkworms spin cocoons in

wooden grids. The worms having been killed, the cocoons, in their frameworks,

were displayed early this year in his Los Angeles gallery. Garnett Puett works

in cooperation with live honeybees to create his apisculptures. I hear rumors

of a man with a pigtail who makes living sculptures with turtles. Someone is

doing something with live crayfish. Regretfully, I force myself to ignore

vertebrates and crustaceans, to hold the line at insects. But then there is a

man with an ant farm he calls art. What is going on?

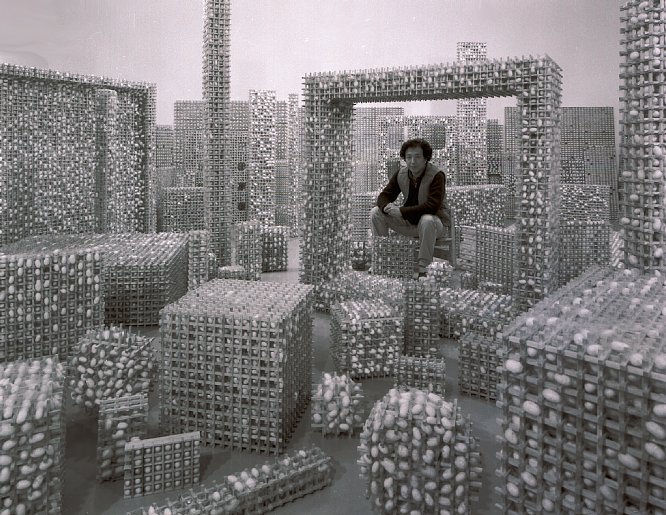

In his show in

February and early March, at the respected Los Angeles gallery Space, Kazuo

Kadonaga displayed nearly a hundred pieces of work, created by a hundred

thousand silkworms. He had fashioned wooden grids, some standing alone, some

stacked, and had released on them silkworms that had been fed until they were

ready to spin cocoons. Silkworms seek protected niches, and these silkworms

explored the wooden gridwork until they found spots to suit them. In the

beginning, Kadonaga gave them freedom to wander as they pleased, but they

bunched together at the tops of the grids and left the bottom niches

unoccupied. So he and his assistant spent forty-eight hours periodically

turning the grids while the silkworms roamed, thereby tricking them into

behaving as though down were up and so was sideways, and the worms settled into

an even, though not uniform, distribution across the grids to spin their cocoons.

(Some niches were never taken by any silkworm, some contained two.) This

amounts to a practical joke on the silkworms, but it is aesthetically pleasing

to the human eye. Silkworms spin threads in an enthusiastic and generous way.

Not only did Kadonaga's make fat silken cocoons, the size of slightly shrunk

Ping-Pong balls, in his grids but they left light, fluffy thread trails as they

crawled to their preferred niches. The completed pieces are a contrast between

the precise, geometric wooden forms and the rounded shapes of the cocoons, the

whole fuzzed up with trailing silk. After the silkworms finished their cocoons,

each piece was heated to kill the worms inside?a process similar to the one followed in sericulture, or silk

farming, when the silkworms must be heated and killed, lest they emerge as

moths and break the long silk threads before a human being can harvest them.

|

Kadonaga's gallery displayed all ninety-one of his pieces

in one divided space where, crowded together, they looked like a cityscape.

It was a witty display?after all, if you are going to ask a hundred thousand

worms to work for you, the total effect is very much to the point?but that

aspect of the show slipped by the reviewers, one of whom, Chuck Nicholson,

writing in Artweek of March 21st, grumbled that the grouping "seriously

detracts from the impact of individual pieces." Being an art critic

must be a sobering job; at least, none of the current critics seem to be

having much fun reviewing Bug Art.

Kadonaga speaks little English and is

only sometimes in this country, but Jeri Coates, who is the assistant director

of Space, reports that he was born in 1946 in Ishikawa-ken, is tall?nearly six feet?

and has long, curly hair. "He has a droll wit," Coates

says. "A puckish sense of humor. He is an actor, a natural mimic, who can

transform himself before your eyes into someone else."

Today, Kadonaga

lives in Tsurugi-machi, near the Sea of Japan, where he is known as Kichigai,

or the Crazy One, partly because he is an artist in a well-to-do family that is

in the lumber business. His father had hoped Kadonaga would join the business,

but he'd decided he wanted to become an artist. He began by painting, but

realized, he said in a 1984 interview, through an interpreter, that

"others painted better." In his father's sawmill he rediscovered

wood, which, he said, "brought out my true artist's personality." He

began to play with it. "I am not creating beauty but discovering the

natural beauty of material," he said in another interview. He sliced wood

into thin layers and allowed it to dry and curl. He scored logs and encouraged

them to check. He made regular grooves in logs and then whacked them with a

samurai sword, and the scored fissures exploded

throughout the interior of the logs to emerge in unpredictable jagged lines on

the other side. He gathered bamboo, frayed it, bent it, arranged it, and called

it art. Handmade paper, a lovely material,

diverted him for a while. He had it made in unusual shapes (triangles, strips,

oblongs), stacked it wet, and clamped it. As the paper dried, the unclamped

portions fluffed up, and he displayed the pieces in a 1983 gallery show. All

this was before he got to silkworms. A catalogue of his shows from the pre-silkworm

period has been published and contains somewhat precious, dramatic, and

seductively gorgeous photographs, which, in effect, become an aspect of his

work.

Kadonaga has had shows in Japan as well as in the

Netherlands, Mexico, Germany, Sweden, New Zealand, and Australia. "In

Japan, they have turned their back on his art,

because they don't know what to make of this man," Edward Lau, the director of the Space gallery, says. Lau believes

that Kadonaga's work is at once too traditional and

too unusual for Japanese buyers. The Japanese,

says Lau, have always understood the beauty of the natural materials Kadonaga

is using, but Western buyers are just beginning to discover it. The silkworm pieces, which, at least to someone of my

entomological bent, are the wittiest of all, draw on a long and reverent

tradition of sericulture in the Far East.

Sericulture dates

back to the early part of the fourth century in Japan and has even more ancient

beginnings in China. As should be expected in the light of its long history, traditions and rituals have grown up

for every stage of silk production, from the care and feeding of the silkworms

to the harvesting of the thread from the cocoons they spin. The worms and also

mulberry leaves, which the worms feed upon, are common motifs in Eastern art. In Japan, as late as the nineteen twenties,

there was a silkworm god who was honored at family altars when the silkworms

finished eating and began to spin.

Resonances of

these reverent traditions are lost on an American audience; our agriculture is

short on reverence and long on getting directly to the bottom line with hogs,

cattle, and soybeans. (There have, however, been moments in American farming

history when sericulture became a fad?eighteenth-

and nineteenth-century versions of today's boutique agriculture.) Instead,

there are other resonances for American buyers. John Pleshette, an actor and

writer, who has bought Kadonaga wood and paper pieces, would have liked to buy one of the silk ones, but his wife,

he told me, finds anything that has to do with insects repellent, so he didn't.

He admitted that the gallery full of them was "kind of eerie," but

went on to say, "Still, the impact was so strong because they had been

living things. The feeling was there that maybe they weren't dead after all.

That was part of the aesthetic. If they weren't

insects but cotton balls, say, the pieces would not have had the same impact. I

think Kadonaga is taking nature and putting some limits on it but preserving

its essential zeitgeist."

The gallery offered

Kadonaga's pieces separately?titled

collectively "Silk" and identified within that collectivity by

numbers and letters?at prices

ranging from three hundred dollars to five thousand dollars. The most expensive

piece that has been sold to date was priced at twenty-five hundred dollars. The

unsold pieces?many of them large

ones, which require a museum setting?are

now stored in a studio in downtown Los Angeles which Kadonaga uses as a base

for his American visits.

"People feel

creepy about bugs anyway," John Pleshette concluded.

*

We are on very slippery anthropomorphic

ground here, and to me what is going on seems something much simpler. These Bug

Artists are messing around with materials, and that is an interesting thing to

be doing. In addition, they're having a rather good time, and that is even

better. What their work has to say is something so plain and obvious that it

seems surprising that it needs saying at all, but since so many people are

engaged in creating artifacts that do say it and no one else is smiling,

perhaps it does: We live in a world in which there are many live things other

than human beings, and many of these things can seem beautiful and amusing and

interesting to us if they can catch our attention and if we can step back from

our crabbed and limiting and lonely anthropocentricity to consider them.